|

| "Me he equivocado y no volverá a ocurrir" |

1.- ¿Por

qué serían paradojales las relaciones entre la corrupción y la culpa?

La paradoja empieza con la idea de que los corruptos

son siempre los otros y que eso nunca es responsabilidad mía. Sigue con la idea

de que el corrupto lo es con el único fin de un beneficio y de un goce propios.

Y sigue todavía más con la idea de que el corrupto nunca se siente responsable

de ello, de que es alguien totalmente sin escrúpulos, sin sentimiento alguno de

culpa, alguien que goza como nadie con el beneficio de su secreta corrupción.

Si esto fuera tan cierto, la historia no estaría tan sembrada de corrupción

explícita, de una corrupción muchas veces socialmente permitida, cuando no

promovida desde la propia política. Alguien tan “políticamente correcto” como

Winston Churchill pudo decir, no sin cierto cinismo, aquella frase que he

citado y que hoy ningún político osaría defender: “Un mínimo de corrupción

sirve como lubricante benéfico para el funcionamiento de la máquina de la

democracia”. O también: “Corrupción en la patria y agresión fuera,

para disimularla”. ¿Se justifica así la corrupción? El problema

no es tan sencillo, pero todos hemos escuchado casos de corrupción llevada a

cabo con las mejores de las intenciones.

Quienes han estudiado el fenómeno, como Carlo

Brioschi en su “Breve historia de la corrupción”, han tenido que ponerse a

cierta distancia de algunos prejuicios. No ha habido, en efecto, ninguna época

de la historia sin una gran dosis de corrupción en los distintos ámbitos

sociales y políticos. Y esta extensión de la corrupción viene siempre

acompañada de un secreto sentimiento de culpa. Corrupción y sentimiento de

culpa parecen así una pareja inseparable. Entonces, cuando este vínculo se hace

demasiado evidente, la paradoja nos conduce hacia el polo opuesto: “¡Todos

corruptos, todos culpables!”. Mire si no las primeras páginas de los periódicos

de cada día.

La paradoja se mantiene en la medida en que creemos

que la corrupción no supone en ningún caso un sentimiento de culpabilidad,

sentimiento que según Freud es siempre inconsciente. El ideal del corrupto, el

corrupto perfecto sería alguien que no sentiría en ningún caso ni un gramo de

culpa, es decir un verdadero perverso. Los hay, es cierto, pero no tantos como

creemos entre los que se consideran social o políticamente corruptos. Aunque

cuando aparece alguno, también es cierto que no hay quien lo pare.

Por otra parte, el verdadero culpable, el que siente

un intenso sentimiento de culpa, no sabe nunca verdaderamente de qué es

culpable, como en los mejores personajes de Kafka. Tanto es así, que existe una

especie, mucho más extendida de lo que creemos, diagnosticada por el mismo

Freud como “delincuentes por culpabilidad”. Son los que delinquen o se

corrompen para satisfacer un sentimiento inconsciente de culpa. Y los hay, se

lo aseguro, los psicoanalistas los escuchamos a veces en los divanes, pero

también pueden encontrarse casos en algunas historias de delincuentes conocidos,

y en ejemplos de corrupción política reciente.

2.- ¿Podría

usted ampliar la idea de que en los países de tradición luterana los estragos

de la corrupción son menores que en los de tradición católica? Esa idea, ¿nos

condenaría a los países del sur? ¿Y qué pasa en los EEUU?

Parece un hecho constatado por encuestas de este

tipo, aunque no siempre sean ajenas a los fenómenos que pretenden denunciar con

la elaboración de sus rankings internacionales de corrupción. En todo caso, es

cierto que hay una importante diferencia entre la lógica del discurso católico

y la lógica del discurso protestante con sus respectivas tradiciones. La

tradición católica de la confesión de los pecados y de su posterior absolución,

—por supuesto, siempre en el ámbito privado del sacramento de la confesión—,

propicia sin duda la impunidad del goce. Puedo permitirme mejor una falta si

preveo su confesión y su posterior absolución, algo absolutamente fuera de

lugar en la tradición protestante que abomina de la confesión, especialmente de

la confesión privada.

Pero solemos ver hoy también este fenómeno en el

ámbito público de los medios de comunicación. Cada vez queda mejor, por decirlo

así, confesar públicamente ya sean los errores, las faltas o los supuestos

pecados. Y cuando no se hace o se intenta negar la culpa, se paga un precio.

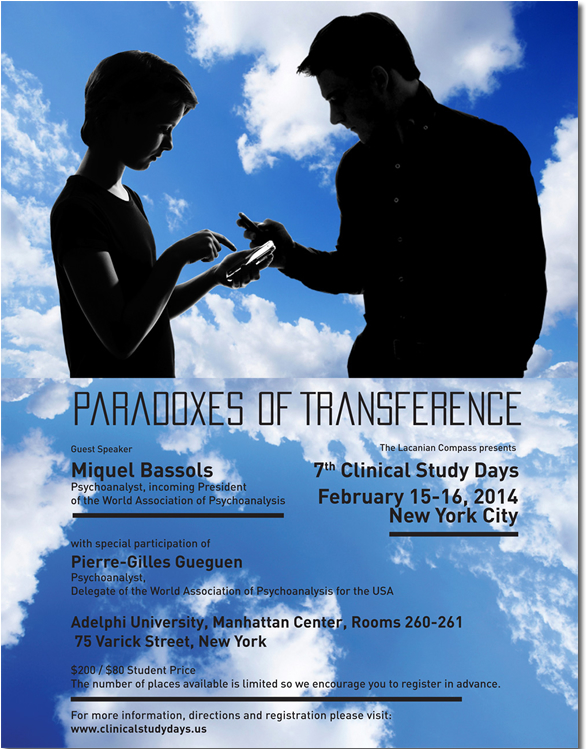

El caso reciente del Rey Juan Carlos apareciendo en

la televisión española pidiendo disculpas con su “me he equivocado y no volverá

a ocurrir”, después de haberse hecho pública su afición a la caza de elefantes,

es un ejemplo de ello. En realidad, era un desplazamiento de los casos de

corrupción que han ido apareciendo en el seno de la propia familia real. Todo

ello ha ido a la par de la caída de uno de los “semblantes” —como decimos los

lacanianos—, uno de los símbolos mayores que sostuvo la llamada transición

democrática española, el símbolo de la propia monarquía. La disculpa pública,

impensable en una monarquía de antaño, ha tenido cierto efecto, entre patético

y pacificador.

El caso reciente de François Hollande en Francia

intentando separar lo público y lo privado con el descubrimiento de su

infidelidad es un ejemplo inverso. De hecho, en Francia, estos asuntos no eran antes

tomados tan en serio públicamente. Las infidelidades de Miterrand no produjeron

por ejemplo tanto escándalo, y hasta su esposa pudo elogiarlas un poco:

“François era así, era un seductor”.

En los temas vinculados con la corrupción está

ocurriendo algo similar. También se pasa a veces del mayor escándalo a la

complacencia más secreta. Hay cierta hipocresía social al respecto.

En todo caso, y para añadir más diferencias a las

distintas tradiciones que articulan faltas, corrupciones y culpas, no debemos

dejar de lado al Japón, donde la tradición shintoista implica una relación con

el honor que puede hacer imperdonable seguir viviendo después de haberse

descubierto una falta por corrupción. El honor japonés parece preferir el

suicidio a la simple confesión pública o a la impunidad del goce.

Dicho esto, hay que señalar que el fenómeno llamado

de la “globalización” está difuminando cada vez más las fronteras entre países

y tradiciones, entre costumbres del norte y costumbres del sur, entre

orientales y occidentales. Estamos ya en la época de la “post-humanidad”, como

ha dicho Jacques-Alain Miller en alguna ocasión, donde la primera corrupción, la

más generalizada, sea tal vez la corrupción del lenguaje mismo a escala global.

Hay palabras que pierden su poder evocador, hasta de interpretación.

3.- Usted

dice que el tráfico de influencias o prebendas está sancionado socialmente (en

las formaciones luteranas) pero después dice que "comprada" la

absolución, ésta puede tomar un matiz mimético, sin respetar tradiciones. ¿Cómo

sería eso?

El tráfico de influencias está sancionado

socialmente, incluso en el sentido de prohibido, pero en muchos casos también

está regulado de forma más o menos institucionalizada. A veces, forma parte de

manera explícita de lo que se da en llamar “el sistema”, y de ahí la idea tan

extendida de que no hay corrupción en el sistema sino que el sistema es

la corrupción. Pero no es por mimesis o imitación que eso se propaga. Lo que

los estudiosos del fenómeno de la corrupción llaman “ley de reciprocidad”

responde al hecho de que, —especialmente en política económica pero no sólo en

ella—, no hay ningún favor desinteresado, nada se hace por nada. Gozar de una

prebenda estará entonces siempre justificado y la supuesta reciprocidad se

contagia entonces como un ideal muy singular, según el cual cada uno piensa que

debe gozar de lo mismo que goza el otro. ¡Si el otro puede gozar de ello yo

también! Este es por otra parte el principio de la publicidad, y también el

principio de la corrupción. Pero en realidad no hay nada tan singular, tan

irrepetible y tan inimitable como el goce de cada uno, empezando por el goce

sexual. Es lo que Jacques Lacan llamó el goce del Uno. Y esto es algo que

atraviesa siglos y tradiciones, lenguas y fronteras, y cada vez de manera más

rápida en nuestro mundo de realidades virtuales. Cuando uno ve en qué se gastan

a veces los beneficios de la corrupción, la cuestión tiene un lado tragicómico.

Es la inutilidad del goce.

4.- Se lo

pregunto (también) a la luz de la teoría del "chivo expiatorio" que

desarrolló René Girard.

El deseo que está en el principio de los vínculos y

conflictos humanos no puede reducirse a la mera imitación de un modelo en el

sentido de la “mimesis” a la que se refiere René Girard, fenómeno imaginario

que puede darse también en los animales. Un animal puede imitar una conducta,

aprenderla siguiendo un modelo, pero esto no quiere decir que esté habitado por

un deseo, que pueda llegar a subjetivarlo, que pueda dividirse ante él o

incluso rechazarlo como un parte de sí mismo. En este punto, la famosa fórmula

de Jacques Lacan, “el deseo es el deseo del Otro”, va mucho más allá de la idea

de un “deseo mimético”—aunque piense inspirarse en él— e introduce una lógica

más compleja sin la cual creo que no pueden entenderse las paradojas de las

relaciones entre los seres humanos, ni el amor, ni el odio, ni la segregación.

Para empezar, este deseo del ser que habla es ya equívoco de entrada, no tiene

un modelo ni una norma, y es tan singular que no hay modo de imitarlo. El

sujeto histérico es el que más intenta identificarse con este deseo del Otro,

pero resulta que esa es a la vez su mayor fuente de insatisfacción. Este deseo

del Otro es tanto el deseo del sujeto hacia el Otro como el enigma del deseo de

este Otro hacia el sujeto.

No, no es por imitación como funciona el deseo ni

tampoco el fenómeno de la corrupción. Más bien funciona por el contagio de una

forma de goce, lo que es muy distinto.

La idea de Girard del “chivo expiatorio” es de hecho

una forma de entender la necesaria segregación del goce del Otro, ese goce que

siempre nos parece bárbaro, distinto, heterogéneo, hasta llegar al racismo. Hoy

el chivo expiatorio puede ser el inmigrante, pero también la mujer maltratada.

5.- Si la

corrupción es un hecho de estructura, ¿será acaso porque el sistema de

jerarquías que ordena una sociedad jamás es igualitario?

Por supuesto, la jerarquía no será nunca

igualitaria. La corrupción puede entenderse por este sesgo, siguiendo un eje

vertical en las relaciones sociales de poder. Pero la corrupción es también y sobre

todo un fenómeno vinculado al reconocimiento entre pares, entre sujetos de una

misma clase, sea cual sea esa clase, siguiendo su horizontalidad y según la

“ley de reciprocidad” a la que antes aludíamos. Muchas veces la propuesta de

corrupción es más una afirmación de igualdad y de reconocimiento entre pares

que no de afirmación de una diferencia en la estructura jerárquica del poder.

Hay aquí una paradoja difícil de tratar: cuanto más

homogéneo e igualitario se pretende un grupo, más segregación interna se

produce, más tendencia a la corrupción podrá encontrarse entonces. Es algo que

Lacan anticipó de manera absolutamente sorprendente en los años sesenta, cuando

el ideal comunitario, especialmente el de la Comunidad Europea, parecía la

promesa de una integración en condiciones ideales de igualdad, incluida también

la Europa del Este. El resultado es en la mayor parte de los casos una feroz

segregación interna y un aumento notable de las críticas a la corrupción

generalizada. Pero el mismo Claude Lévi-Strauss se encontró un poco abucheado

al defender la necesaria diferencia y la separación de las poblaciones para

mantener una convivencia soportable entre formas de gozar diferentes. La

igualdad forzada por un lado retorna como diferencia segregada por el otro.

Parece un virus para el que no encontramos antídoto.

El psicoanálisis propone una ética del deseo, lo que

supone siempre una pérdida de goce, y eso es siempre una buena vacuna contra la

corrupción.

6.- ¿Es

posible que los chinos se hayan contagiado también? ¿Cómo pensar una absolución

(un goce) "comprado" en la tradición confuciana?

Y sí, China ha entrando ya de lleno en el contagio,

no hay duda alguna. Y además de una manera que parece mucho más eficaz, es

decir, posiblemente mucho más arrasadora para la subjetividad de nuestra época

porque la propia transacción de bienes, por ejemplo, no es entendida de la

misma forma. Pruebe a negociar con un comerciante o con un empresario chino, no

terminará de saber nunca si se ha cerrado o no el acuerdo. Es al menos lo que

me comentan empresarios catalanes para los que las cosas deben estar siempre

muy claras: al pan, pan… Tal vez la tradición del confucionismo, que según Max Weber

toleraba mucho más que otras tradiciones una gran variedad de cultos populares

sin proponer un sistema cerrado, esté en el principio de esta facilidad de

contagio que es a la vez signo de una gran flexibilidad. Pero aquí de nuevo,

por muchas puertas al campo que se quieran poner, como con el endurecimiento de

la censura en Internet por parte del Gobierno chino, el contagio del lenguaje y

de las formas de goce está asegurado. Y veremos adónde nos llevará…

7. - Seguro usted leyó la nota sobre las fortunas que

algunos jerarcas chinos han escondido en ciertos paraísos fiscales. ¿Qué

relación tiene esa cultura con la culpa y el goce, que es lo que queda sin

responder en "Maonomics", el libro de Loretta Napoleoni?

No he

leído todavía el libro de Loretta Napoleoni. La idea de que el “nuevo”

comunismo chino puede ser mucho más eficaz, —eficaz también, por supuesto, en

el peor de los sentidos—, que el “viejo” capitalismo occidental puede parecer

sorprendente. Un neocapitalismo de trabajadores ideales, dispuestos a trabajar

masiva y solidariamente sin sentirse explotados porque encuentran las promesas

de su Estado realizadas de manera rápida, puede ser una maquinaria tan infernal

como efectiva. Lo interesante es que todo ello parecería fundarse en la

eficacia de un Estado-Padre que interviene sin contemplaciones en los mercados,

sin dejarlos seguir la pendiente de su supuesto principio de autorregulación,

ese “principio del placer” —en términos freudianos— que se nos ha vendido en

Occidente como la mejor de las leyes del aparato psíquico-financiero. Y es

cierto, el principio del placer, el supuesto principio homeostático de los

mercados, fracasa por definición, tal como hemos comprobado de manera

especialmente trágica durante estas últimas décadas. Es el fracaso del

principio del placer descubierto por Freud y del que Lacan extrajo la nueva

economía del goce, la economía de lo inútil. El fracaso del principio del

placer parece tener un vínculo estrecho con la crisis de los Estados-Padre. ¿Cómo

no evocar aquí de nuevo ese “declive de la imago paterna” que Jacques Lacan

diagnosticaba hace ya unas cuantas décadas en Occidente como uno de los

factores más sintomáticos de su malestar?

Pero,

en fin, tampoco hay nada bueno que esperar de cualquier intento de restauración

de esta figura de “Un Padre”, sea en el Estado que sea. Tampoco en China.

En todo

caso, hay seguramente algo que aprender de todo esto, especialmente en la nueva

y vieja Europa: era más lógico haber partido de una unidad política que no de

una comunidad económica y monetaria como ha sucedido con el euro y los tratados

de Maastricht. Pero es también más prudente partir de la diversidad de las

identidades en juego que de la homogenización impuesta por la identificación

con “Un Padre”.

La

pluralización de los Nombres del Padre indicada por Lacan como un dato de la

clínica psicoanalítica es un signo de nuestra era. Pero esto daría para otra

entrevista.